A man I know—let’s call him Justin—finds himself accused of non-consensually touching a woman I don’t know. There are banishments from places they once both used to go. There are rustlings of legal action and a crusade by the woman to expose him as a predator.

I know Justin well and like and respect him. And I don’t doubt that this woman is telling her truth.

I meet up with Justin to talk and walk.

“I think I know what happened here,” I tell him after initial pleasantries.

“Do enlighten me, ‘cause this is fucked. There were a bunch of us there, just chilling in the park, and everyone was doing massages on everyone else. I massaged her leg. She was on her belly on a blanket and she didn’t say anything to me. She didn’t ask me to stop. She even made sounds and movements like it felt good.”

I take a breath into a queasy feeling in my guts.

Y’all, I have been that woman so many times.

Maybe you have, too.

I’ve been the woman who lets a man touch her or massage her or have sex with her and only afterwards realizes that her true experience was one of violation.

Right there, with Justin, on a gorgeous trail surrounded by eucalyptus trees, beside a rain-swelled creek, I’m transported into a memory of my gawky, pre-pubescent 12-year-old self being literally dragged across the floor by a much gawkier older boy toward his bedroom while our four parents ate dinner upstairs.

Unable to protest or run away. Frozen.

In the aftermath of subsequent episodes of mysteriously losing my ability to enact a boundary, I used to get so mad…at myself. “What was I thinking?” I’d fume. I’d call myself a slut and feel dirty and ashamed. I’d think the guy was awful and taking advantage of me even as I knew I’d clicked into some weird kind of auto-pilot that made me just go along—even feign enthusiasm—to avoid rejecting someone.

Since then, I’ve learned through study of psychology, emotions, and brain science about what probably transpires in the brain and body of a person who has such an experience.

Old brain, new brain

We stop to admire the rushing water. The air is redolent with eucalyptus and jasmine.

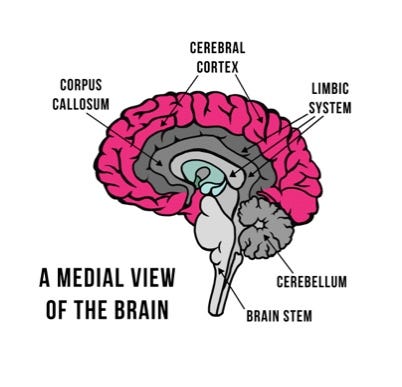

“The nervous system has two parts,”1 I continue. “There’s one part that is responsible for identifying threats and cueing up the response to threat that’s most likely to restore safety: fighting, fleeing, freezing, or fawning. I’ll explain those in a minute. Let’s call that part the ‘old brain’ because it’s primitive—it evolved early and it exists in pretty much every critter that has a brain.”

“Old brain. Got it.”

“If you wanna get fancy, you can call it the limbic system. Its only M.O. is to identify any source of danger and to escape it. Then there’s this other part that is unique to humans…let’s call it the ‘new brain.’ The cerebral cortex. What do you think the new brain does?”

“Well, I guess it must be…higher brain functions. Like thinking, inventing, looking at the future or thinking about the past?”

“Exactly. It’s the thinking, reasoning part of the brain.”

Here comes the flood

We keep walking, our feet making lovely soft sounds on the trail.

“Let’s say the old brain detects a threat. It might be, you know, a car speeding toward you as you step into a crosswalk. The old brain shoots out a signal to the adrenal glands, these little walnut-shaped jobbies that sit on top of the kidneys. The adrenals then pump out a hormone called adrenaline, which signals the whole system to fight, flee, or freeze—whichever one is most likely to resolve the threat.

“Let’s call this being flooded,” I go on. “When we’re flooded, blood and oxygen all get shunted within a split second to fuel muscles and heart and lungs. Our heart rate goes up past 120 beats a minute to prime the body to get out of danger. We might feel hot, or get sweaty or twitchy or jumpy, like we just had a bunch of caffeine.2 The new brain, the thinking brain, is temporarily under-fueled. It takes a backseat so the organism can preserve itself. You act fast and think it through later, when the adrenaline has been processed out of your system and your new brain comes back online.”

“Sure. You don’t want to be weighing the pros and cons of getting out of the way of a moving car. You gotta either stop short—freeze, yes?—or get real big and yell and wave your arms to get the driver to stop…”

“Right. That’s fight.”

“...or flee, run or jump out of the way.”

“Exactly. This is a good thing when there’s a real acute threat. But our old brain isn’t very good at differentiating between real acute threats and threats that are not so acute or real. Its one job is to react fast to any possible threat. A fight with a partner, an upcoming exam, having to speak in front of a group, feeling rejected or disrespected, thinking about something that scares us or makes us angry when it isn’t even happening right now or to us, someone touching us without our consent…all can be read by the old brain as threats that can trigger us to fight, flee, or freeze, and to temporarily lose the ability to act according to our hard-earned wisdom, the boundaries we want to set for ourselves, or our core beliefs about right and wrong.”

…Our old brain isn’t very good at differentiating between real acute threats and threats that are not so acute or real. Its one job is to react fast to any possible threat.

“Are you saying that this woman felt threatened by me, and so she froze?”

“Kind of.”

“That’s fucked up. I was not being threatening with her in any way.”

Where the man in the story is forced to see that maleness can be inherently threatening

“Let’s say I, a female person, have had a history of sexual trauma, or have often been touched when I didn’t want to be. Maybe that one time I said ‘NO’ real strong, some man with a lot of power over me got all butt-hurt and defensive or outright angry or rejected me, and that had some real negative impact on my life. Maybe my creepy uncle had a habit of tickling me when I didn’t want to be tickled.”

“Ugh,” he says.

“Maybe I’ve just generally had a lot of moments throughout my life where I was in a place I didn’t want to be and for whatever reason I couldn’t get away or advocate effectively for myself. MAYBE I GREW UP A WOMAN UNDER PATRIARCHY, indoctrinated with messages that males should be appeased. Any of these things might lower my threshold for feeling violated and triggering my threat system in response to, oh, I don’t know, UNWANTED TOUCH. So when my new acquaintance Justin decides my leg wants massaging, that threat system is activated.”

“Sure, that makes sense,” he says. “So she was flooded, and that’s why she didn’t tell me to stop. And then later on, when she stopped being flooded, she realized that she felt violated by me.”

“I think that might be what happened, yeah.”

The ‘fawn’ response

Predictably, Justin reminds me that the woman was actively expressing that she liked what he was doing while he was doing it.

I tell him, “When I was 19 years old I met this beautiful man. I had a boyfriend at the time but I was so enamored with this guy that I went home with him. I made out with him. I told him I wasn’t going to have sex with him. I said no and I tried to get away and he overpowered me.

“After he raped me, I got up and went to the bathroom. I did not flee, nor did I fight. I washed my face and fixed my hair and went back into his room. I sat back down on the bed. I let him cuddle me and tell me how much he liked me. I FUCKING LET HIM WALK ME HOME AND KISS ME GOODNIGHT.”

“Wow,” Justin says.

“If I’m under the threat of a strong man wanting me to submit to him, my response might be not only to freeze, but to fawn—to flatter, appease, and please the one who has the power to do me harm. It might be bad already, but my threat response system is acting to make sure it doesn’t get worse.”

If I’m under the threat of a strong man wanting me to submit to him, my response might be not only to freeze, but to fawn…It might be bad already, but my threat response system is acting to make sure it doesn’t get worse.

“So. Friend.” I get real close to him and look him in the eyes. “You cannot necessarily tell in a situation like that whether someone is consenting for real. So maybe slow your roll with massaging strangers.”

“I will.”

HBO series Girls spoiler alert

Episode 3 of the final season of Lena Dunham’s Girls3 focuses solely on a single interchange between Hannah, a 20-something writer struggling to make it in New York City, and a famous, successful older male novelist. The novelist has been accused of non-consensual sexual acts while on a book tour. He has asked to talk to Hannah because of her own published writings excoriating him for this. He wants to convince her that he is not only innocent, but victimized by the world and by her article.

He makes his points well, as does she. Many of the nuances of the male-female power dynamic are beautifully fleshed out through Dunham’s expertly crafted dialogue. By the end, one might be convinced that both sides have valid arguments.

Toward the end of the episode, they chatter about writerly things. He offers her a signed copy of a Philip Roth book, which thrills her. He asks her to lie down next to him on his bed for a moment.

(Watching, I scream, “DON’T DO IT!” at the screen, startling my partner.)

As soon as the request is made, we see her go into what I can only describe as a trance. If I could take this fictional character’s heart rate at this moment, I’m betting it would be above 120 bpm.

She’s flooded. Frozen. Is there a real threat? Is she physically capable of escaping this situation without being harmed? Yeah. But can she really? Evidently not.

She lies down on her back, stiffly, staring at the ceiling. He reaches down and pulls his penis out through the fly of his jeans. She grabs it and holds it for an excruciatingly long moment. And then, she remembers herself. She releases his…member. She leaps to her feet. She shouts at him. We think she’s going to break the cycle. GO HANNAH!

A young voice pipes up from downstairs. It’s the writer’s daughter, who has surprised him with a visit.

The next thing we see is Hannah, having stayed at the writer’s insistence, watching the daughter play the flute. She is back in the trance.

Coming round to the STOPS for this week

Knowing that the fawn response is a defense against threat can help men not get handsy or worse with women they don’t know (you’re welcome, Justin). It can help women understand why we might feel stuck in people-pleasing and conflict aversion. We may WANT to be empowered and assertive…and when the moment comes, and fear overtakes us, we get flooded, and all our good intentions to be kick-ass women might go out the window.

In my work as a therapist, facilitator, and coach, I have seen a lot of women (myself very much included) struggle around self-advocacy. It can be a struggle even to allow ourselves to enact our full brilliance in our lives, relationships, or workplaces…because we might piss someone off in the process.

We have to be willing to piss people off: to shift default patterns to fawning and appeasing. (I am speaking to myself as much as to any of you.)

The strategy:

Start to track your patterns of activation. What gets your adrenaline pumping?

Most of us know a little about which situations make us flooded. Our bodies also give us ‘clues’ that can help us recognize when this is happening. A few examples (you might have others to add to the list):

Heart racing

Breath speeds up

Muscles tense

Twitchy parts (muscles of the face, hands, butt, legs, arms…)

Racing thoughts, can’t focus

Feeling numb

Heat in face or hands

Sweating

Desire to revert to verbal or physical violence

An overpowering need to appease or soothe someone else

Once you identify that you are flooded or nearly so, start to practice the PAUSE.

Really PAUSE.

Maybe the best you can do is just NOT DO ANYTHING. That’s a start. Just STOP and don’t…speak…don’t…problem-solve…just…do…NOTHING.

Next level: get yourself a few actual self-soothing, resource-building strategies.

Let your body breathe more deeply. Soothe yourself: music, squats, cat vids, dancing, hugging, whatever is your jam. Talk ABOUT what your brain and body are doing—a new-brain response to perceived threat—rather than reacting from old-brain default habit patterns. Do some self-research into the source of those defaults.

When you notice your body clues, pause and give the adrenaline a chance to work itself out and your new brain to come back online. Name it. Keep naming it.

Every time we name it, pause, calm, and go back in once our new brain is online, we shift our neural circuitry, making it feel less like a wrestling match and more like a default over time.

Patience is crucial. Pattern interrupts feel wrong and weird for a while, until they don’t.

This is a huge topic and I’ll return to it in future posts. For now: enjoy the springing of spring, wherever you are.

Attribution to Jennifer Freed, PhD and Rendy Freedman, MFT, for these terms, which are drawn from curricula they created for AHA!, the educational non-profit they founded together and ran as co-executive directors for over 20 years.

It is also possible to enter into a state of collapse when we are flooded. This response involves a great slowing-down of the body’s systems rather than an adrenaline-fueled revving-up. Going into more depth on this piece of the puzzle is beyond the scope of this post, but I promise to return to it in a later post.

If you haven’t watched it yet: highly recommend.

Lots of good info 💜